نظام إدارة النفايات الذكي في سيول:معالجة واستعادة الموارد

Issues

Until the 1990s Seoul’s waste management practice was predominantly landfilling, however it could not last forever. With the expansion of the city and its economy, securing available sites for landfill sites became more and more difficult. Faced with Nanjido Landfill Site almost filled to capacity and the increased difficulty of siting process, incineration surfaced as an alternative waste treatment measure. Besides, as an intermediary treatment method before landfilling, it was expected to extend the life of landfill sites by reducing the amount of solid waste.

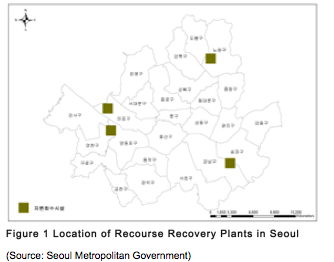

The new state-of-the-art incinerators are called ‘Resource Recovery Facilities.‘ They burn solid urban waste at 850-950℃ to recover the heat (above 400℃) in the process of trash burning. Also the high-pressure steam is used as alternative source of energy that provides heating for the near communities. This is why resource recovery facilities are conceptually different to traditional incinerators. Seoul Metropolitan Government first gave consideration to building resource recovery facilities in the early 1990s and subsequently the construction of four major resource recovery plants was carried out over two decades. Only four districts contain their own resource recovery facilities.

Solution

As mentioned above, there are four resource recovery facilities in the Seoul area in Nowon, Yangchon, Gangnam and Mapo as seen in Figure 9. The first resource recovery facility in Seoul opened in Yangcheon-gu with capacity of 150 tons per day in 1996. Since then, Seoul acquired three more resource recovery plants in Nowon-gu (1997) Gangnam-gu (2001) and Mapo-gu (2005). They process 2,850 tons of household wastes on average every day. Mapo Resource Recovery Plant converts 750 tons of wastes into power on a daily basis and is shared with five administrative districts in the northwest Seoul, namely Mapo-gu, Yongsan-gu, Jung-gu, Jongro-gu and Seodaemun-gu. The Nowon plant, shared with the northeast districts of Nown, Jungnang, Seongbuk, Gangbuk, Dobong and Dongdaemun, has been in operation since 1997 and it treats 800 tons of waste every day. Gangnam plant, in operation since 2001, treats 900 T/day of waste from seven districts in the southeast Seoul. Lastly, Yangcheon plant, established in 1996, takes 400 tons of wastes a day from the southwest Seoul. In all, four resource recovery plants in Seoul are shared with 21 administrative districts. (SMG Climate & Environment Headquarters, 2012)

As mentioned above, there are four resource recovery facilities in the Seoul area in Nowon, Yangchon, Gangnam and Mapo as seen in Figure 9. The first resource recovery facility in Seoul opened in Yangcheon-gu with capacity of 150 tons per day in 1996. Since then, Seoul acquired three more resource recovery plants in Nowon-gu (1997) Gangnam-gu (2001) and Mapo-gu (2005). They process 2,850 tons of household wastes on average every day. Mapo Resource Recovery Plant converts 750 tons of wastes into power on a daily basis and is shared with five administrative districts in the northwest Seoul, namely Mapo-gu, Yongsan-gu, Jung-gu, Jongro-gu and Seodaemun-gu. The Nowon plant, shared with the northeast districts of Nown, Jungnang, Seongbuk, Gangbuk, Dobong and Dongdaemun, has been in operation since 1997 and it treats 800 tons of waste every day. Gangnam plant, in operation since 2001, treats 900 T/day of waste from seven districts in the southeast Seoul. Lastly, Yangcheon plant, established in 1996, takes 400 tons of wastes a day from the southwest Seoul. In all, four resource recovery plants in Seoul are shared with 21 administrative districts. (SMG Climate & Environment Headquarters, 2012)

Because there are only four resource recovery plants in Seoul, the city government decided to share these plants with districts without such amenity. This decision met strong oppositions from the residents who live near a resource recovery plant due to the predominance of negative associations with incineration plant. The city made arrangements such as public hearings and briefing sessions and provided financial incentives for the residents in the areas of influence. By showing its intention to ensure the citizens’ safety and the safe operation of the facilities, Seoul Metropolitan Government was able to persuade the citizens.

As a consequence of joint use, operating rates of the plants jumped from 33% in 2006 to 82% in 2010. The residents in the areas of influence are provided with subsidized heating and other incentives. In addition, some of the profits from the resource recovery facilities go to community support fund. Sharing resource recovery plants brought technological, economic and societal benefits such as extension of Sudokwon Landfill, reduced air pollutants, and lowered costs for heating and transportation of wastes. (SMG Resource Recovery Facility)

2.1. Planning

In April 1991, Seoul Metropolitan Government announced a comprehensive plan for waste management, signaling a transition in waste management policy from landfilling to resource recovery. The decision encountered strong resistance and opposition from residents against siting such facilities in their area and the increase in the amount of waste treated their neighborhood. So an amendment was made in the original plan so that every district would have its own incineration plant, which turned out later to be inefficient and infeasible; half of the districts just did not have any available space. Some worried that building 11 incineration plants would worsen the air pollution problem. As a solution, the city decided that three to four districts would jointly use and operate needed but unwanted facilities. (Choi, 2000)

2.2. Implementation

1) Negotiation with Residents

To overcome public resistance to the joint use of resource recovery facilities, Seoul Metropolitan Government strived to find ways to encourage citizens’ support through over 320 public meetings since 2001. As part of such efforts, related city ordinances were revised over two times to reflect discussions from the talks with residents. According to the amendments made, residents who live within 300 meters from the plants receive a discount of up to 70% on their electricity bill as a means to compensate for their inconvenience and discomfort. In addition, the tipping charge of the resource recovery plants was lowered to the prime cost to encourage cooperation among the authorities at the districts where the plants are located. With regards to the intake of wastes from other districts, consultation should meet requirements set out by three stakeholding parties, namely Seoul Metropolitan Government, district’s head officer and the citizens’ council. Proceeds from the community support fund would be spent to subsidize apartment management fees, medical costs and recreational facility use for the residents in the region. (SMG Resource Recovery Facility)

⦁ Negotiation Process: Construction of Nowon Resource Recovery Plant

The construction of Nowon plant provoked intense opposition from the local residents who feared the dioxin emissions from incinerators and the negative impact of having an incinerator nearby on their property values. To resolve these conflicts, Korean and Seoul Metropolitan Government conducted a negotiation process to address local concerns and communicate with residents the necessity of socially needed facilities. At last, the project earned public support and was given a go-ahead when they realized social benefits of resource recovery and accepted the government’s promise to cut the amount of emissions and provide compensation for their discomfort. (Lim, 2013)

⦁ Negotiation Process: Joint Use of Mapo Resource Recovery Plant

The plan for the joint use of Mapo Resource Recovery Plant, aimed at increasing its operating rates, was not welcomed by the Mapo-gu citizens. Even though, the conflict in this district was relatively easy to settle. The consultation process kicked off with a council established in 1996 which made up of officers from the involved districts and community representatives. In 1997, the council agreed to include Jung-gu in the coverage of Mapo plant. To compensate for the inconvenience from the increased amount of waste processed in their existing facility, Mapo-gu requested for the city’s investment on public amenities such as cycling lanes in their ward. On December 31, 1997 after two days of consultation, Yongsan-gu was approved to join when the agreements were reached among Mapo residents (Lee, 2000)

⦁ Negotiation Process: Joint Use of Yangcheon Resource Recovery Plant

Yangcheon Resource Recovery Plant was built as part of a major housing development in Mok-dong Yangcheon-gu. Originally, the plant was used exclusively by Yangcheon-gu and this was the reason hind its low operating rate. Joint use of Yangcheon plant was first discussed in July 1998 when Seoul Metropolitan Government decided to address the low operation efficiency issue of Yangcheon plant. Stakeholders from different sectors, including civic groups, residents and the involved authorities, were invited to workshops, plant tours and round-table talks. In 2010, the city government finally won approval from the local residents, after four years of efforts to resolve conflicts and misunderstanding among the interested parties. During those four years a variety of strategies were initiated, such 560 public meetings between local representatives and the city authorities. The city government also disclosed data to prove the safety of the resource recovery facility to combat public fear.

According to the agreements made, Gangseo-gu and Youngdeungpo-gu are susceptible to donate 1,000 won every ton of waste they discharge to the Yangcheon plant and subsidize the apartment management fees of the residents living within 300 meters of the facility, along with investments for neighborhood improvement. (e2news, 2010; Newsis, 2010) Besides, some of the proceeds from increased heat production from the joint use go to the residents, providing 8.8% discount on heating bills. The city government has also conducted health impact assessments on the operation of the facilities since 2000. In addition, to relief for the residents’ concern over dioxin emissions, standards were raised for emissions, ten times more stringent than national standards. Residents are allowed to monitor the concentrations of pollutants through the automated monitoring system. (Newsis, 2010)

2) Citizens’ Council

The city government allows the residents in the area to build a citizens’ council that consists of the community representatives, members of the district council, and specialists in environmental sciences recommended by residents. It is entitled to appoint a research institute to conduct the environmental impact assessments of the resource recovery facility and monitor whether the facilities operate in an environmentally healthy manner. They represent community’s interests by ensuring adequate compensations for the discomfort caused by having unwanted facilities. (SMG Resource Recovery Facility)

2.3. Finance

1) Operation Costs and New Revenues

The construction of Nowon Resource Recovery Plant totaled at 62.7 billion won, entirely financed with city budgets and its operation costs are also borne by Seoul Metropolitan Government. Back in 2006 before the join use agreement, annual operation costs was 6.1 billion won whereas the revenues from waste collection and heat production was merely 2.1 billion won, incurring almost 4 billion won of deficit every year. Likewise, the Yangcheon plant used to find itself in deficit, with annual operation expenses of 4.5 billion won and revenues of 2.4 billion won. As of 2009, it is operating at about 81% of the designed capacity, a dramatic jump from 33% in 2006. (The Hwankyoung Sisa Ilbo, 2006)

Converting waste into energy to provide electricity and domestic heating replaces 104.1 billion won of energy imports every year while cutting down 594,608 tCO2 of greenhouse gas emission. The four resource recovery plants in Seoul, equipped with SCR catalyst systems, save annual LNG costs of 5.8 billion won, thus reducing the city’s annual greenhouse gas emissions by 15,000 tCO2. The shortened travel distance from wastes to treatment facilities is responsible for saving transport costs by 5 billion won every year. (The Energy Economic News, 2011)

2) Community Support Fund

Under the city ordinances, a community support fund was created from the gains generated from the operation of resource recovery facilities. Used for improving the living environment in the areas of influence, the fund is raised with 10% of the revenues from tipping charge collection (extra 10% on wastes from the user districts), and donations from the user districts. Under Enforcement Decree on Promotion of Installation of Waste Disposal Facilities and Assistance to Adjacent Areas Act, the proceeds from the fund is spent to subsidize heating bills, apartment management fees, medical expenses and other community welfare related service and projects approved by the fund management committee.

According to the joint use agreement, Gangseo-gu and Youngdengpo-gu are liable to donate 2,1000 won per one ton of waste discharged to Yangcheon Resource Recovery Plant and subsidize heating bills of 3,413 households residing within 300m from the facility. 10% of the revenues from tipping charge collection including extra 10% levied on wastes from the user districts goes toward the community support fund. The residents get some of their living expenses subsidized including heating bills and apartment management fees by the community support fund. Likewise, Mapo-gu received handouts from Jung-gu (KRW 6.6 billion) and Mapo-gu (KRW 4.8 billion), who are liable to donate 20% of tipping charge to Mapo Development Fund for sharing its resource recovery plant. (Lee, 2000)

2.4. Challenges

It is only Mapo Resource Recovery Plant which was built under the joint use plan. The other three resource recovery plants in Seoul originally only served the district where it lies and struggled with low operating rates of 20~30%. To address this low operation efficiency, making these plants available to neighboring districts was considered necessary to extend the life of Sudokwon Landfill Site. Yet the city government’s decision to increase waste management efficiency was met with strong resistance from the residents who did not want any increase of the waste treated in the facility in their district.

To settle civil resistance, Seoul Metropolitan Government strived to seek ways to encourage citizens’ support through over 320 public meetings since 2001. Besides, related city ordinances were revised over two times to reflect discussions from the talks with residents. According to the amendments made, residents who live within 300 meters from the plants receive a discount of up to 70% on their electricity bill as a means to compensate for their inconvenience and discomfort. The tipping charge of the resource recovery plants was lowered to the prime cost to encourage cooperation among the authorities at the districts where the plants are located. As for the intake of wastes from other districts, consultation should meet requirements set out by three parties, namely Seoul Metropolitan Government, district’s head officer and the citizens’ council. Proceeds from the community support fund would be spent to subsidize apartment management fees, medical costs and recreational facility use for the residents in the region. (SMG Resource Recovery Facility)

Results

3.1. Output

1) Improved Operation Efficiency of Resource Recovery Facilities

The partnership has effectively maximized the use of the facilities to meet demands. In addition to creating more opportunities for the respective districts, sharing four resource recovery facilities between twenty administrative districts within Seoul has led to positive impacts in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and replacing energy imports.

The method for waste treatment underwent substantial changes. In order to manage the limited national land efficiently, the government has widened the policy scope to waste management away from the heavy reliance on landfilling. Consequently, the expected life of Sudokown Landfill Site has been extended.

Due to the increased shares of incineration, the expected life of Sudokown Landfill Site has been extended until 2044. (e2 news, 2010). The joint use system led to a huge improvement in operating rates of the plants, jumping from 33% in 2006 to 82% in 2010. Moreover, surplus heat from the incineration process is also utilized as an alternative energy source.

| Yangcheon | Nowon | Gangnam | Mapo | |

| Region | Southeast | Northeast | Southeast | Northwest |

| Capacity | 400 t/day (200 t/day ×2 incinerators) |

800 t/day (400 t/day ×2 incinerators) |

900 t/day (300 t/day ×3 incinerators) |

750 t/day (250 t/day ×3 incinerators) |

| Construction Period | 1992.12~1996.2 | 1992.12~1997.1 | 1994.12~2001.12 | 2001.12~2005.5 |

| Joint-use Agreement Date |

2010.5.10 | 2007.6.30. | 2007.5.7. | 2009.2.10. |

| Site area (㎡) | 14,627 | 46,307 | 63,813 | 58,435 |

| Construction Cost (KRW million) | 31,815 | 74,279 | 101,080 | 171,166 |

| Sharing Districts | Yangcheon-gu Gangseo-gu Youngdeungpo-gu |

Nowon-gu Jungnang-gu Seongbuk-gu Gangbuk-gu Dobong-gu Dongdaemun-gu |

Gangnam-gu Seongdong-gu Gwangjin-gu Dongjak-gu Seocho-gu Songpa-gu Gangdong-gu |

Mapo-gu Yongsan-gu Jung-gu Seodamun-gu |

| Amount of Waste Burned (2005) |

131 t/day | 147 t/day | 212 t/day | 443 t/day |

| Amount of Waste Burned (2012) | 345 t/day | 614 t/day | 835 t/day | 635 t/day |

| Operating Rate (2005) | 32.8% | 18.5% | 23.6% | 59.1% |

| Operating Rate (2012) | 86% | 77% | 93% | 85% |

Figure 3 Joint Use Status

2) Economic and Environmental Benefits from Resource Recovery

The Seoul‘s recovery facilities burns 740,000 tons of solid municipal waste and has recovered 1.76 million Gcals of environment-friendly energy. The amount is enough to provide heating for 200,000 households, approximately 15% of Seoul’s apartments, for one year assuming the annual heating figure of 9Gcal.

Behind such a remarkable improvement was the doubled recovery rate compared to that of year 2006. (Energy Economic News, 2011) The recovered energy can also substitute oil imports that amounts 104.1 billion won every year. In addition, by recycling wastes that would otherwise be landfilled, CO2 emissions are saved annually by 594,608 tons.

3.2. Outcome

1) Prevention of Greenhouse Gas Emissions

By employing SCR catalyst system, Seoul’s resource recovery plants have saved annual LNG costs of 5.8 billion won; thereby cut the city’s annual greenhouse gas emissions by 15,000 tCO2. Such accomplishment in reducing greenhouse gas emissions indeed gained wide praises, with Nowon Resource Recovery Plant being formally recognized as ‘a government agency with contribution to the promotion of greenhouse gas emissions’ at ECO-EXPO KOREA 2013. (Voice of the People, 2013) Converting waste into energy to provide electricity and domestic heating replaces 104.1 billion won of energy imports every year and cuts 594,608 tCO2 of greenhouse gas emissions. The four resource recovery plants in Seoul, employing SCR catalyst systems, save annual LNG costs of 5.8 billion won. The shortened travel distance from wastes to treatment facilities is another contributor, saving transport costs by 5 billion won every year. (The Energy Economic News, 2011)

2) Increasing Public Awareness on Waste Treatment Facilities

Yangcheon Green Environment Education Center focuses on Seoul’s environmental policies such as contemporary waste-to-energy facilities, air pollution management, car-sharing service and the future waste management system called Dust Bot. It also offers hands-on learning experience to help citizens understand the facility’s waste treatment process. It also runs a variety of educational programs for citizens to foster a better understanding of the environment and the resource recovery facility. (Seoul Times, 2012) Seoul Metropolitan Government runs citizen monitoring system and supports citizens’ council to resolve distrust of citizens while making continuous investments on community facilities. As a consequence, there has been a remarkable change in the understanding and trust of the public. In addition to employing monitoring personnel to monitor fraudulent activities, honorary citizen monitors were appointed. They received education to help guide citizens in adapting to the new way of waste disposal.

Lessons Learned

1) Overcoming the NIMBY through Community Support

Regarding the installation or joint use of resource recovery plants, Seoul Metropolitan Government showed sufficient capacity to facilitate agreement among residents and promoted ways to engage them by arranging a civic council and citizen monitors. In addition, a community support fund was established for community improvements and residents’ needs were promptly reflected through communication with community representatives. All of these hard works is shown in increased local trust and awareness of the benefits of resource recovery facilities.

2) Improving Maintenance and Operation

As to overcoming public distrust in the authorities’ capacity to provide safe service, openness turned out to be the key. Disclosing data on the facility operation, stipulating and reflecting residents’ requests, establishing resident monitor system was involved on the path to build a climate of trust. In order to overcome persistent negative associations with resource recovery plants and disruption to residents they may cause, the city yet need to make further investments on facilities such as anti-pollution system, green space and exterior designs.

3) Circular Economy via Waste-to-energy Initiatives

Unlike regular incinerators, resource recovery plants utilize surplus heat from combustion of wastes at a temperature between 850℃ and 1100℃ to provide heating in the region. Waste-to-energy initiatives are Seoul’s way of paving the path to the circular economy. Seoul’s case has proved the world retrieving energy from waste not only can substitute reliance on fossil fuel and landfilling, but can be source of profits.